|

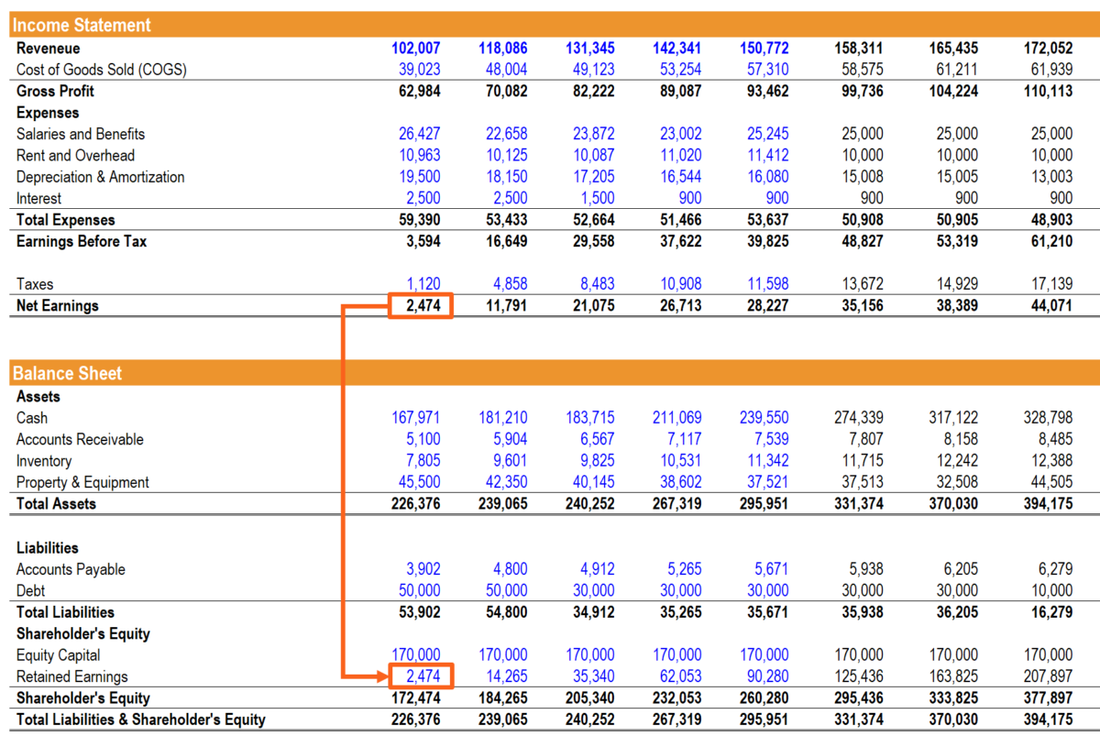

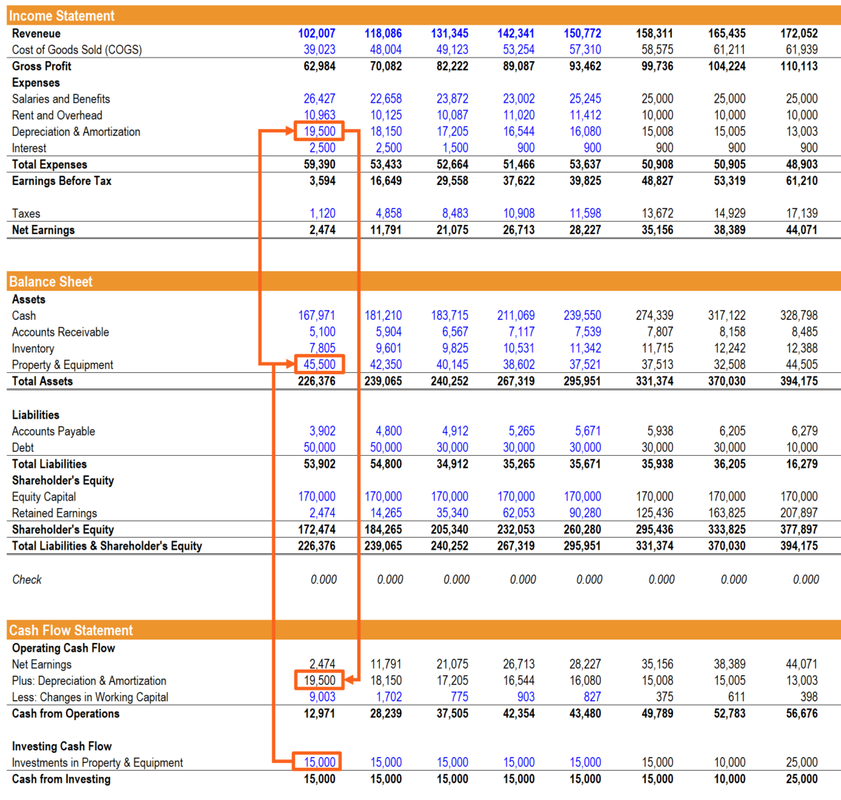

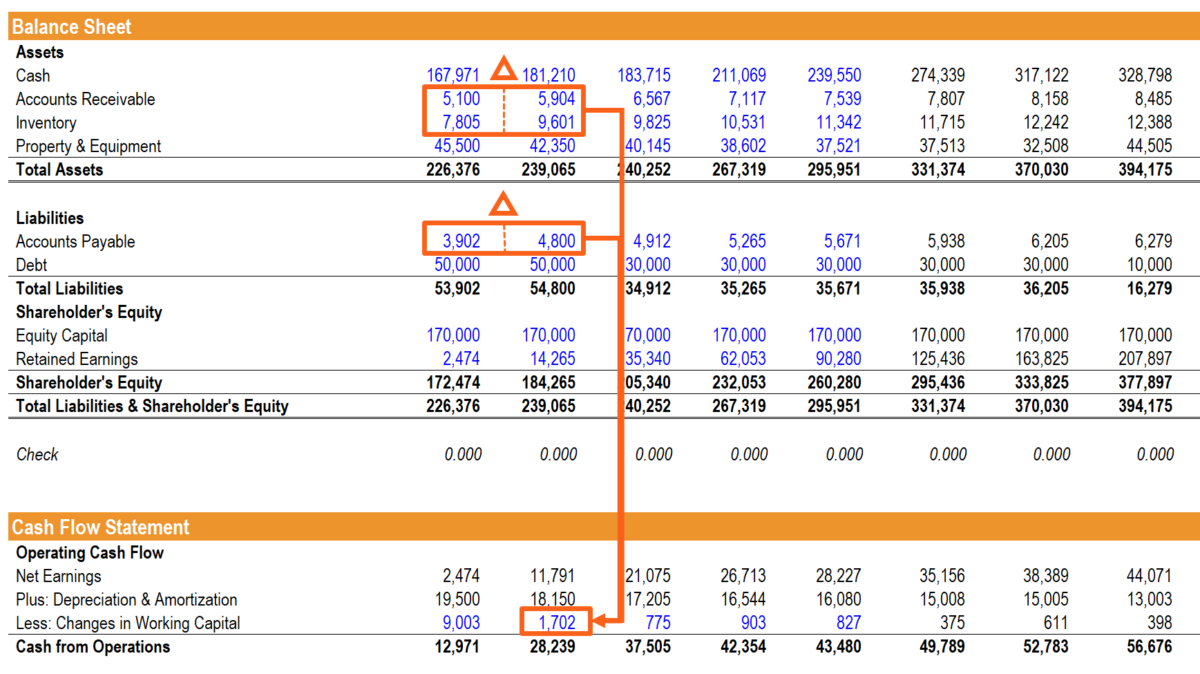

Net Income & Retained Earnings Net income from the bottom of the income statement links to the balance sheet and cash flow statement. On the balance sheet, it feeds into retained earnings and on the cash flow statement, it is the starting point for the cash from operations section. PP&E, Depreciation, and Capex Depreciation and other capitalized expenses on the income statement need to be added back to net income to calculate the cash flow from operations. Depreciation flows out of the balance sheet from Property Plant and Equipment (PP&E) onto the income statement as an expense, and then gets added back in the cash flow statement. For this section of linking the 3 financial statements, it’s important to build a separate depreciation schedule. Capital expenditures add to the PP&E account on the balance sheet and flow through cash from investing on the cash flow statement. Working Capital Modeling net working capital can sometimes be confusing. Changes in current assets and current liabilities on the balance sheet are related to revenues and expenses on the income statement but need to be adjusted on the cash flow statement to reflect the actual amount of cash received or spent by the business. In order to do this, we create a separate section that calculates the changes in net working capital. It's critical to understand how certain events in your business will change these statements and lead to changes to your bottom-line. Let Us Help. Call MRB Now.

3 Comments

April 1 could be costly for older retirement account owners. No fooling.

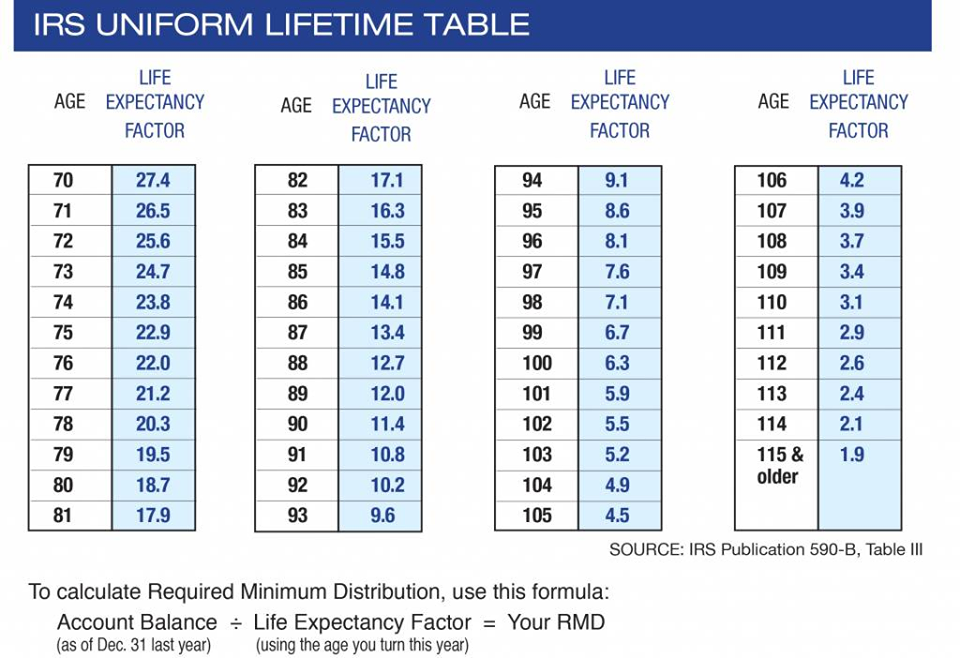

That's the deadline for taking a required minimum distribution, or RMD, if you turned 70½ last year and did not take the specified amount from your tax-deferred retirement funds by Dec. 31. RMDs are required amounts that you must withdraw from a retirement plan that's been earning money over the years without you having to pay tax on it. The tax law has been letting these accounts ride for years, decades in many cases. But when you get halfway through your 70th year, the Internal Revenue Service says enough. Uncle Sam is tired of waiting for his tax cut on these accounts and you must now start taking out some of the savings and paying the tax. If you don't, you could be hit with a substantial tax penalty. If you're among those facing an RMD for the first time, either this rapidly approaching April 1, or by the end of this year, here are 10 questions and answers that could help you fulfill this tax task. 1. What types of retirement plans require minimum distributions? The RMD rules apply to all employer-sponsored retirement plans, including profit-sharing plans, 401(k) plans, 403(b) plans, and 457(b) plans. The RMD rules also apply to traditional IRAs and IRA-based plans such as SEPs, SARSEPs, and SIMPLE IRAs, as well as to Roth 401(k) accounts. However, the RMD rules do not apply to Roth IRAs while the owner is alive. 2. When must I receive my required minimum distribution? You must take your first required minimum distribution for the year in which you turn age 70½. However, the first payment can be delayed until April 1 of the year following the year in which you turn 70½. For all subsequent years, including the year in which you were paid the first RMD by April 1, you must take the RMD by Dec. 31. If you did turn 70½ last year, but aren't taking your RMD until this year (by the April 1 due date), remember that you'll need to take another RMD by Dec. 31 to cover this year's RMD. If you've yet to his your RMD age, you'll want to run some numbers before then to determine the potential tax cost of delaying that first required withdrawal into the next year and then having to take two RMDs in one year. Since most of us don't celebrate half-year birthdays (but, just saying, maybe it's something to consider), keep in mind the June 30-July 1 calendar page turn. Basically, if you were born in the second half of the year (July 1 or later), you get a full year before you have to worry about an RMD. For example; Jane was born June 15, 1948. That means she turned 70½ in December 2018 and must take an RMD for the 2018 tax year, either by last Dec. 31 or by April 1st 2019. Her husband Joe, however, was born July 15, 1948, meaning that Joe didn't turn 70½ until January 2019, giving him all this year or until April 1, 2020, to make his first RMD. These half-year date determinants apply even if you're born at 11:59 p.m. on June 30 or and at 12:00 a.m. on July 1. Also, even if you've been taking money from a tax-deferred retirement account (or accounts) before you hit your RMD half-birthday, once you do turn 70½ you must begin calculating and receiving at least the annual mandated amount. 3. May I take more than one withdrawal in a year to meet my RMD? Yes, you can spread out your required withdrawals as you see fit to meet your tax and personal finance goals as long as you withdraw the total RMD minimum by Dec. 31 or April 1 if it is for your first RMD. 4. How do I calculate my RMD amount? If you have multiple tax-deferred retirement savings plans, you must calculate the RMD for each. Generally, this is done by taking each account's value on the prior Dec. 31 (your plan's annual statement should show this) and dividing that amount by a life expectancy factor that IRS publishes in tables in Publication 590-B, Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs). Choose the life expectancy table to use based on your situation. They are: -Joint and Last Survivor Table - use this if the sole beneficiary of the account is your spouse and your spouse is more than 10 years younger than you -Uniform Lifetime Table - use this if your spouse is not your sole beneficiary or your spouse is not more than 10 years younger. This is the most commonly used table. That's why I recreated it in this blog post. -Single Life Expectancy Table - use this if you are a beneficiary of an account (an inherited IRA) The IRS provides worksheets to help you with your calculations. MRB Accounting can also help you figure out what you owe. RMDs are another good reason to hire a tax professional who works with you year-round. 5. Does it matter which accounts are tapped to pay the annual RMD? While you must figure each retirement plan's RMD separately, you don't have to take the mandated money out of each. You can withdraw the total amount from one or more of the IRAs. Similarly, a 403(b) contract owner must calculate the RMD separately for each 403(b) contract that he or she owns but can take the total amount from one or more of the 403(b) contracts. However, RMDs required from other types of retirement plans, such as 401(k) and 457(b) plans have to be taken separately from each of those plan accounts. This could be another reason why you might want to look at rolling a 401(k) from a former employer into an IRA. 6. Does tax law limit how much I can withdraw from any or all of my retirement accounts? No. The IRS obviously wants to take its bite out of your tax-deferred accounts, hence the minimum withdrawal rule. But if you want or need to take out more than your year's RMD, that's your choice. You can't, however, credit one year's excess withdrawal amount toward a future RMD. 7. How is your RMD taxed? Distributions from a tax-deferred retirement account are taxed as ordinary income. This means the tax rates and brackets you use when you figure the tax on regular income, such as wages, apply. This is an unwelcome surprise to many folks who think that since their retirement money was in an investment account, the distributions are taxed at the usually lower capital gains tax rates. One bit of good news is that if you ever made nondeductible contributions to your traditional IRA, not all of the distribution from that account is taxable. The bad news here, though, is that you should have kept good records of these nondeductible contributions. Remember the Form 8606 you filed every time you made nondeductible contributions to your traditional IRA? Dig those out. It's the official tax record that will keep you paying federal income tax twice on the same money, i.e., the IRA contributions that you didn't deduct. 8. Are there restrictions on what I can do with my RMD? The only rule is that you cannot put this retirement money into another tax-deferred retirement account. That is, you can't take the money from an affected plan and, if you don't need it, put it into another existing retirement account. If you don't need all your RMD to cover your living expenses, put the excess into another investment account. That way, the money will continue to earn and this time it will be taxed at potentially lower capital gains rates when you do take out the earnings more than a year later. 9. Are there ways to avoid tax on an RMD? As noted in question/answer #6, part of your RMD could be tax-free if you made nondeductible IRA contributions. There's also an RMD exception if you're still working when your turn 70½. In this case, RMDs from your tax-deferred workplace retirement plan can be delayed until you actually retire. Note, however, that the RMD is postponed only for that employer's retirement plan. You still must take your RMD from any other tax-deferred retirement accounts. Then there's the qualified charitable distribution (QCD) option. You still must take out your RMD, but when that's coming out of a traditional IRA, you can have up to $100,000 of the distribution delivered directly to an IRS-qualified charity. This is a good move if you don't need the retirement plan money to live on. By sending it directly to your preferred charity, you still meet your RMD for the year but the money doesn't count as taxable income. Even better, you don't have to worry if you've made both deductible and nondeductible contributions to your traditional IRAs. A special rule treats amounts distributed to charities as coming first from taxable funds, instead of proportionately from taxable and nontaxable funds, as would be the case with regular distributions. And if you're married and file a joint return, your spouse can also make his or her own direct IRA donation of up to 100 grand. 10. What's the penalty for not taking an RMD? 50 percent of what you should have taken out for the year. To put that in alarming dollars, let's say you were a diligent saver and ended up with $1 million in your traditional IRA when you turned 70½. Your first RMD is $36,496 (see question/answer #3). If you don't withdraw that amount, your tax penalty is $18,248. Plus, you still must pay income tax on the full amount that was supposed to be withdrawn under the RMD rule. And there's no statute of limitations on missed RMDs, meaning when the IRS catches your oversight, you'll owe the big bucks plus interest. The IRS could waive the penalty if you can show that your RMD shortfall was due to reasonable error and that you're taking reasonable steps to make things right. To get RMD penalty relief, file Form 5329 and attach a letter of explanation. You can find more in the form's instructions. Your best move, however, is to know when you'll face RMDs and make tax and financial moves to comply with the withdrawals. Let Us Help. Call MRB Now. |

AuthorArchives

March 2020

CategoriesThe NY Accounting, Tax and Advisory Expert Blog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed